HongKong Moss Machine

2019 | Green Topia | HongKong

Kurator: Andrew Lam Hon Kin

Visualisierung: R.H.

Concept for a Hong Kong Moss Machine to Green Topia

Train of Thoughts by Rolf Hinterecker

For thousands of years, people lived in huts and buildings made of natural materials such as bamboo, clay, wood, etc., which weathered after a certain time. The temples and tombs, which were mostly made of stone, were also subject to weathering, depending on the region and climate. A vegetative infestation of lichens (Borobodur / Indonesia), mosses (Peru) or a complete overgrowth (Angkor Wat) belong to the cultural history of architecture. Especially the colonial buildings in the tropics offered numerous points of attack for a diverse flora.

Ferns and small trees belonged to the townscape of most colonial cities and were accepted as natural sometime. Even the first concrete buildings of the Romans started to have a vegetative patina.

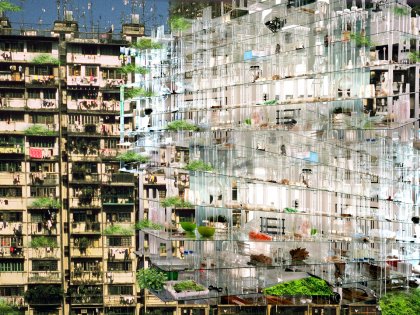

Only the skyscraper facades in the urban centres of modern times set new standards. With their aesthetic elegance, there is no space for moss and mush. The vegetation is implanted into the buildings in elaborate art landscapes with palm trees and waterfalls. Outside, war was declared on nature. Especially in office and administration buildings with their large mirror and glass facades, the level of chemical use for cleaning and energy consumption rose.

Mega-cities and metropolises are therefore in the special focus of the climate discussions.

The idea of the moss machine is a philosophical consideration or an impertinence.

Despite all its glorified beauty, nature also consists of diseases, death and other ugliness. The rotting of vegetative material provides the breeding ground for insects, these in turn, etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc.. When offices plan this "beautiful new world" with their specialists, from nature design to climate engineering, and use the tools of scientific and technical possibilities, the naivety with which they underestimate the virulence of biological and climatic processes is also fascinating.

The question if we all should do what we could do is increasingly asked - not least against the background of the current global warming discussions ->Friday for future.

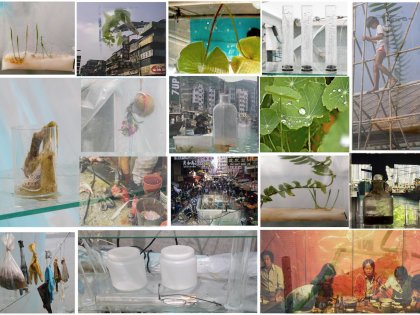

Moss machines anarchically green the facades of buildings, industrial halls and other objects such as highways, bridges, etc. that store heat.

The moss is spat out - its seeds* are blown out and released as a water mist.

The exact function is unclear, since the experimental arrangement of the laboratory devices are themselves living organisms that lead their own lives.

There is a high risk that the release of the moss will cause the entire city to fall into a kind of green sleep and the facility managers will be busy cutting observation slits into the facades.

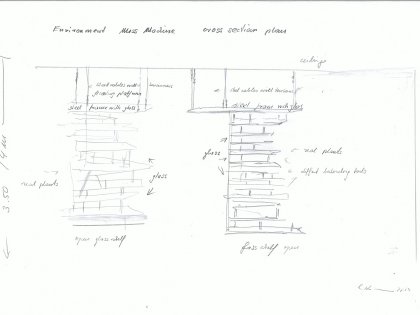

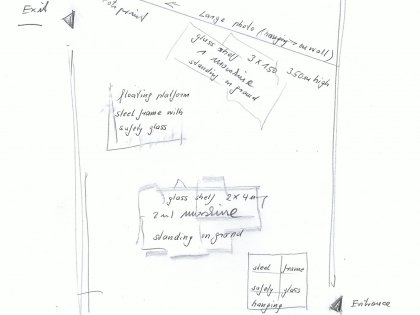

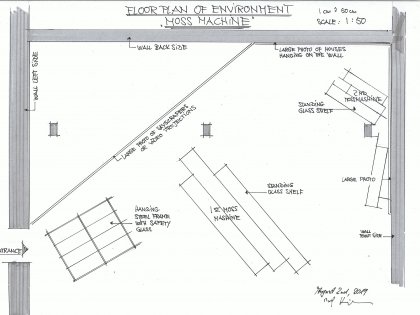

Walk-in laboratory equipment, installation and environment with various organs.

Biological background

Reproduction of moss

The role of sexual reproduction in increasing genetic diversity is considerably limited in mosses. About half of the mosses are monoecious and predominantly self-pollinated (no self incompatibility). In addition, many diocesan species occur only in purely female or purely male populations and cannot reproduce sexually.

The relatively low probability that the spermatozoids will reach the archegonia in water for fertilisation is compensated by the fact that in such a case very large numbers of spores are usually produced. Dawsonia holds the record with five million spores in one sporangium. Several hundred thousand are also not rare in other species. The spores are very widespread, mostly much further than the actual art areas. Therefore, many mosses can react very quickly to climatic changes and colonize new, suitable habitats.

DNA repair

The moss Physcomitrella patens has been used as a model organism to study how plants repair damage to their DNA, especially the repair mechanism known as homologous recombination. If the plant cannot repair DNA damage, e.g. double-strand breaks, in their somatic cells, the cells can lose normal functions or die. If this occurs during meiosis (part of sexual reproduction), they could become infertile. The genome of P. patens has been sequenced, which has allowed several genes involved in DNA repair to be identified.[20] P. patens mutants that are defective in key steps of homologous recombination have been used to work out how the repair mechanism functions in plants. For example, a study of P. patens mutants defective in RpRAD51, a gene that encodes a protein at the core of the recombinational repair reaction, indicated that homologous recombination is essential for repairing DNA double-strand breaks in this plant.[21] Similarly, studies of mutants defective in Ppmre11 or Pprad50 (that encode key proteins of the MRN complex, the principal sensor of DNA double-strand breaks) showed that these genes are necessary for repair of DNA damage as well as for normal growth and development.